Tracy Alloway strikes one of the more ridiculous trades in commodities history.

Don't buy a barrel of oil," the broker said. "It'll kill you."

A fortuitous meeting between a gas trader and his broker at a bar in downtown New York was not going the way I had hoped. After revealing a long-held plan to try to buy a barrel of crude, I was now receiving a disappointingly stern lecture on the dangers of hydrogen sulfides. The wine tasted vaguely sulfuric, too.

Oil may be king of the commodities, but its physical form is tough to come by for a retail investor. Mom and pop can buy gold and silver. They can gather aluminum cans, grow soybeans, and strip copper wiring, if they choose, but oil remains elusive—and for very good reason. Oil, as I would soon discover, is practically useless in its unrefined form. It is also highly toxic, very difficult to store, and smells bad.

A sample of Bakken crude, journeyed by railcar from a well in North Dakota to the Philadelphia refining complex on the East Coast.

If gold is the equivalent of a pet rock, then I can confidently say that oil is the equivalent of playing host to a herd of feral cats; it demands constant vigilance and maintenance. If gathered in sufficient quantities, it will probably try to kill you, or at least severely harm your health.

"Sharks off the British Coast"

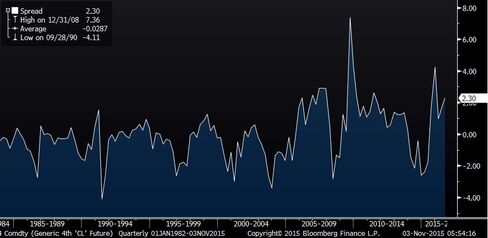

The story of how I came to own physical oil begins in late 2008, when fallout from the financial crisis spurred the crude market into severe contango—meaning the price of oil for future delivery was higher than the expected price of immediate “spot” delivery. While contango is the usual and persistent state of the oil futures curve, this particular "super" version helped create the perfect conditions for an almighty oil storage trade as the price of crude for future delivery vastly eclipsed the cost-of-carry and storage expenses of petroleum bought in the spot market.

In other words, those with the capacity to move and store crude oil could make a pretty penny simply by buying the stuff on the cheap, putting it away, and selling it for a higher price at a later date.

Many of them did so and, for a period of time, the technical vagaries of the oil market made headlines in even the most mainstream of media. "Sharks off the British coast: Oil tankers refuse to unload until prices rise … keeping YOUR fuel costs soaring," Britain's Daily Mail screamed in 2009, describing the "waiting game" played by oil profiteers near the English shore.

I wanted to see if I could be such a shark. A plan was soon hatched with some ex-colleagues to source a barrel of oil and store it—all in the name of journalistic experimentation. (Market reporters rarely get to engage in the sort of gonzo journalism enjoyed by our nonfinancial brethren. Where Hunter S. Thompson had motorcycle gangs and Halcion, we must content ourselves with mineral rights and hydrocarbons.) In the end, our organizational skills proved lacking, and the recovery in oil prices soon made the super-contango story a thing of the past.

It was not until a chance meeting in a Tribeca winebar during an evening thunderstorm many years later that the oil barrel plan was revived—to its less than receptive audience. Whereas West Texas Intermediate had been trading at $145 a barrel at its peak in 2008, it was, in October 2015, now hovering closer to $47 a barrel following an almighty re-evaluation of global demand and supply.

Petroleum, I reasoned, had for all intents and purposes just gone on sale. And while the super-contango was long gone, the oil futures curve was still sloping upward. Profits, albeit meager ones, were still there for the taking.

The WTI futures curve in late 2009 and now in November 2015. The more upward sloping the stronger the 'contango"

"Don't buy a barrel of oil," the broker repeated after I had outlined my reasoning, declining the offer of my business with grim finality. The gas trader nodded sagely. Lightning flashed behind him. A waitress appeared, suddenly and bearing many wine lists, at our table.

The additional Riesling helped turn things around.

A trip was soon arranged to the tidal strait of Arthur Kill, where crude oil is stored, blended, and refined on its way to becoming such wondrous things as nylons and synthetic leather. (This would prove important, as an unfortunate meeting with an exposed nail and an uneven dock would ruin a perfectly serviceable pair of work shoes on this trip.)

Here, just a few miles south of the Statue of Liberty, is a whole new world of floating industry. Rusty oil tankers slip past the slick cooling towers of power generators to unload petrochemicals.

“You will be dead”

On a 42-foot fishing boat, the broker and I traveled with a handful of his clients (mostly French, mostly well-behaved) for a viewing tour of New Jersey’s finest oil terminals.

"Could a barrel of crude really kill me?" I asked a petrochemical engineer captive to my persistent, doubtlessly annoying questions. It absolutely can, he said. Hydrogen sulfide gas—H2S, for short—has a terrible propensity to evaporate from crude, knock out your olfactory capabilities, and slowly suffocate you to death.

Further research conducted by iPhone, somewhere in the Raritan Bay, turned up this gem (PDF) from a state safety agency: “If you inhale ethyl alcohol vapors in a concentration of 1,000 ppm (0.1 percent by volume) for eight hours, you may get drunk. If you inhale hydrogen sulfide in a concentration of 1,000 ppm (0.1 percent by volume) for only a few seconds, you will be dead."

It is at this point that I conceded defeat. Storing oil, it turns out, requires incredibly good ventilation and a rock-solid insurance policy, both severely lacking at my 400-square-foot New York apartment. While Bloomberg LP's headquarters might prove more suitable on both counts, I doubted my ability to roll 100 pounds-plus of highly-toxic liquid in a bright blue barrel past the building's notoriously strict security guards.

All was not lost, however. If a barrel of crude oil would kill me, a small amount would certainly make me stronger, I suggested (inanely) to the broker. It was at this point, I believe, that the broker gave up.

A well-known oil inspection company was called and a respectable-size bottle of crude procured, soon to wing its way to Manhattan via FedEx. It would come by rail from the Bakken Formation in North Dakota to the Philadelphia refining complex on the East Coast. I have named it Williston—a reference to the petroleum-rich basin that dominates the Northern Great Plains and an homage to the loss of my own sanity as I pursued this harebrained scheme. (Willliston! Williiiistooon! I shall cry, à la Tom Hanks in Cast Away, when I finally part with the thing.)

By my calculations, this jar of oil is worth approximately 24¢ on the spot market. In March, it will be worth 31¢, based on futures prices. My storage costs are zero and my financing costs are low, so I expect to be able to pocket a whopping 7¢. My boss insists that I must factor in the cost of lost productivity for the many minutes spent on the phone with FedEx in an attempt to trace the package as it zigzagged across Manhattan. On that basis, I’m probably already in the red.

“Well done for supporting ISIS”

Much more productivity was to be lost finding a buyer, however.

The ideal oil storage trade works something like this: Buy the crude and immediately agree to deliver it at a later date, thereby locking in the difference between the spot and futures prices for what is, in theory, a riskless profit. In 2008, when the forward price of oil vastly eclipsed the spot price, this kind of arbitrage could net a hefty return.

The difference between first-month and fourth-month WTI crude oil futures reached a high in late 2008.

A true oil storage trade therefore required an early buyer. The usual suspects—think Glencore and Trafigura—wouldn’t dream of touching my puny amount of oil, of course. So I looked farther afield, all the way to my ex-colleagues, who I thought surely still harbored those dreams of owning Black Gold.

Izabella Kaminska, a writer for FT Alphaville and an all-round commodities expert, expressed interest in the contract, then immediately embarked on a due diligence process that would make me rue the whole endeavor.

Unsatisfied with photos of the product, she recruited the services of a professional oil consultant for comfort. The consultant asked for a full inspector’s analysis report and a proof-of-origin certificate. All I had was a FedEx invoice, though I assured them both that I wouldn’t dream of peddling anything but top-shelf sweet crude.

“That [is] all good and well until you learn it’s not Bakken but Kurdish oil, under strict embargo. Well done [for] supporting ISIS,” the consultant replied by e-mail. Adding insult, the consultant informed me that the glass bottle was worth more than the oil inside it, anyway.

When I threatened to sell the oil to a far-friendlier former FT colleague, one without expert knowledge of commodities or the benefit of a sarcastic oil professional, I was accused of taking advantage of less-informed retail investors. Expletives followed.

Many e-mails later, the deal was struck. Crude would be delivered in March to the FT’s New York offices. I can bring it personally, thereby preserving my already slim profit margin; it is a far more convenient consignment spot than Cushing, Okla., the physical delivery hub for North American crude.

Kaminska insists on paying me by blockchain, the digital ledger system that is currently all the rage on Wall Street. I fear I am now exposed to substantial default risk.

(Whatever profit I ultimately make from my few drops of oil is nothing, compared with the $2.25 payday I could have generated from trading an entire barrel. For those wondering, this is how I would have done it: Across the state line in Pennsylvania, a few small-scale petroleum producers remain in a town called Titusville. This is a place steeped in oil history and where—I am reliably told by my new network of physical crude trader contacts—it is possible to bring your own barrel and fill 'er up. It is literally BYOB, though not as we may remember it from college.)

In the meantime, however, I am happy with my pint-size pet oil. I keep it in the dark, away from open flames. I shake it once in a while to prevent the contents from settling.

My Brooklyn-based colleagues joke that I am just a few short steps away from starting an artisanal oil refining company. (“Home-grown gasoline sourced from the finest liquefied remains of prehistoric organisms.”) My Wall Street contacts quip that the new presence of "dumb money" in the physical oil market must surely mean that petroleum’s already precipitous slide has farther to go. The broker is almost certainly happy to have lost this particular client.

No comments:

Post a Comment