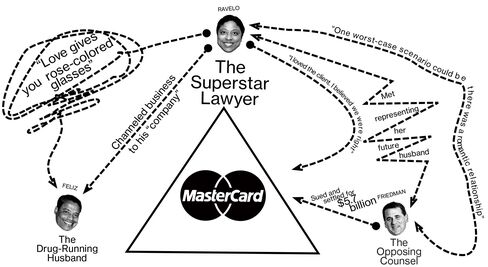

MasterCard’s record settlement with merchants is unraveling after one of its lawyers was found secretly communing with the other side

Keila Ravelo and her husband, Melvin Feliz, were asleep in their prairie-style home in Englewood Cliffs, N.J., three days before Christmas 2014 when 20 federal agents charged through the front door with guns drawn. The show of force met no resistance. Ravelo and Feliz submitted to being handcuffed and were driven away in unmarked government sedans.

Keila Ravelo and her husband, Melvin Feliz, were asleep in their prairie-style home in Englewood Cliffs, N.J., three days before Christmas 2014 when 20 federal agents charged through the front door with guns drawn. The show of force met no resistance. Ravelo and Feliz submitted to being handcuffed and were driven away in unmarked government sedans.

Ravelo, 50, had never been arrested before. A partner with the elite New York corporate law firm Willkie Farr & Gallagher, she’d built a successful career as a litigator, primarily representing MasterCard against waves of price-fixing lawsuits filed by retailers. In one credit card case, she helped negotiate a $5.7 billion truce—the largest settlement of an antitrust class action in the world. Earning more than $2 million a year, she favored Hermès handbags and diamond jewelry. She owned a Bentley Continental Flying Spur sedan and sent her teenage sons to a high-priced boarding school in Florida. Feliz, 49, had a varied past that included stints in real estate, paralegal work, and narcotics trafficking.

Husband and wife were taken to federal court in Newark and formally charged with a series of peculiar felonies. Prosecutors alleged that for years Ravelo and Feliz had ripped off her law firm and MasterCard in an $8 million scheme whereby Feliz provided phony back-office services. The crimes carry potential prison terms of more than 10 years. And there was another surprise.

After federal prosecutors subpoenaed Willkie, looking for evidence of the phony-vendor scheme, Ravelo’s colleagues went through her e-mails and discovered she’d been secretly and inappropriately communicating with the enemy: a plaintiffs’ lawyer named Gary Friedman who was suing MasterCard and other major credit card companies on behalf of thousands of retail stores. Concerned about conflicts of interest, Ravelo’s firm decided to disclose the communication publicly. By mid-2015 the Friedman-Ravelo e-mails threatened to undermine the $5.7 billion settlement against MasterCard and Visa. In August a federal judge in Brooklyn, N.Y., rejected a parallel settlement involving American Express, citing the e-mails to Ravelo, at least two of which Friedman marked “Burn after reading.”

It turns out that Ravelo and Friedman had known each other for a quarter-century—since they met as young attorneys representing none other than Melvin Feliz, who’d been convicted on cocaine charges. Ravelo fell for her client, a fellow immigrant from the Dominican Republic who convinced her he’d change his ways. Feliz declined via an attorney to comment. In an exclusive interview, Ravelo says she was fooled long ago, and is now paying the price. “Love,” she says, with resignation in her voice, “gives you rose-colored glasses.”

Ravelo’s story has a can’t-make-this-stuff-up quality: She rose from working-class beginnings in the Caribbean, put herself through law school at Columbia, and reached the highest level of the legal profession, only to get tripped up by scandal. The tale illustrates the strange vicissitudes of greed (prosecutors’ version), the power of romance to cloud common sense (Ravelo’s version), or some combination of the two (perhaps the most likely version). “I still can’t believe how it all unfolded,” says Friedman, who now has career troubles of his own.

Beyond its personal dimensions, the account pulls back the curtain on mass litigation, a process with more line-blurring than is typically revealed in court. Defending herself against criminal fraud charges, of which she says she’s not guilty, Ravelo unmistakably threatens to implicate other lawyers in what she says are the seamy aspects of class-action settlement negotiations. “If I have to show the ugly side to prove my defense,” she says, “that’s what I’ll do.”

Small in stature, Ravelo has large eyes and a gleaming white smile. Former colleagues and opponents, many of whom demanded anonymity because of the controversy engulfing her, describe her as a feisty attorney who scuffled over issues large and small. No one doubted her fealty to clients; her competitiveness with fellow attorneys, however, frequently exceeded her congeniality.

Growing up in the Dominican capital of Santo Domingo, Ravelo attended private schools, even though she says her parents struggled to house and feed their five children. Around age 11 she gained fluency in English during an 18-month stay with relatives in New York City. She returned to New York at 17, determined to attend college in the U.S.

Ravelo worked as a supermarket cashier, saved money while applying for a green card, and eventually enrolled at Upsala College, a now-defunct liberal arts school in northern New Jersey. She played on the volleyball team and studied hard. Her ambition and intelligence carried her to law school at Columbia, from which she graduated in 1991. She went straight to work in the New York office of Sidley Austin, a prestigious Chicago-based corporate firm. Ravelo recounts her progression with understandable pride. Unlike some of her legal contemporaries, she says, “nothing was handed to me.”

At Sidley, she met Friedman, a more senior associate, while handling a pro bono case on behalf of three convicted Dominican American cocaine dealers. The trio, small-time street sellers, claimed in a civil suit against the federal government that they’d suffered severe beatings by U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration agents. “Gary latched onto me because of the shared Dominican background and my Spanish-language skills,” Ravelo says. “He liked my energy”—an assessment Friedman confirms. Sitting at the civil trial as “second chair” for the plaintiffs, she grew enamored of Feliz. “We both had family in the Bronx,” she says. “He felt like family.”

Feliz came from a middle-class Dominican clan; for high school, his parents had sent him to the Valley Forge Military Academy in Pennsylvania. He told Ravelo he got caught up in drug dealing as a 19-year-old and regretted it, she says. “I was putting a picture together in my head, and I believed it—that the crime is not what defined him.” A New York jury didn’t buy the civil suit against the DEA, and Feliz headed off to prison on the cocaine charge.

During three years behind bars, Feliz obtained a community college degree and promised Ravelo he’d learned his lesson. In 1995 he got out, and they married. The following year they moved from the Bronx to tony Englewood Cliffs. Feliz, who’d become something of a jailhouse lawyer helping other inmates with their appeals, took a job with Friedman as a paralegal. “He worked hard and had big goals to start a business of his own,” says Friedman, who’d formed a small private practice. Friedman and his wife, a law professor in New York, socialized with Feliz and Ravelo. “We loved Mel and Keila,” he says.

Ravelo’s legal career took off as she moved from Sidley to another well-established firm, Rogers & Wells, where she won a coveted partnership based not on her courtroom genius but her tireless management of behind-the-scenes discovery, according to several lawyers familiar with her work. Like most large-firm litigators, she rarely appeared before juries or even argued motions to judges. Instead, she took and defended pretrial depositions and wrangled over voluminous document exchanges. She earned a reputation not only for meticulously preparing “depo” witnesses but also for jousting tenaciously over even the most peripheral procedural matters.

Ravelo didn’t include her husband in socializing related to work, with the exception of the Friedmans. “His past was going to be a problem with my colleagues,” she says. “While I was able to figure out he was a good guy, I didn’t think that other people in my professional world would be able to avoid being judgmental and critical.”

She’s probably correct. In the late 1990s, Feliz went back to prison for eight months on a perjury conviction related to his testimony during the civil suit against the DEA. “It was horrific,” Ravelo recalls. “This is not the sort of thing you see at big corporate law firms.”

For her part, Ravelo flourished, largely because of her antitrust work for MasterCard, a company besieged by allegations it conspired with banks that issue cards and rival card networks to fix interchange fees, also known as swipe fees, that are charged to merchants for the privilege of using plastic. Overlapping suits filed by thousands of large and small retailers also alleged that the card networks and banks unlawfully prevented retailers from using surcharges to discourage consumers from using more expensive cards.

“It was horrific. This is not the sort of thing you see at big corporate law firms”

Ravelo says her loyalty to MasterCard went beyond legalities: “I loved the client. I believed we were right. I lived it day and night.” She became a regular presence at MasterCard’s headquarters in Purchase, N.Y., and a confidante of the company’s top in-house lawyer, Noah Hanft, who controlled tens of millions of dollars in annual legal spending. (Hanft declined to comment.)

In 2005 the Richmond (Va.)-based firm of Hunton & Williams recruited Ravelo to join a growing antitrust department, and, in a reflection of her growing influence, she brought MasterCard along as a client. At this point, with Feliz about five years out of prison, Ravelo says her husband’s career interests began to intersect with her own. Feliz and his brother and sister-in-law had started a small document-copying business catering to lawyers, she says. As digital-document management replaced the reproduction and storage of physical paperwork, Feliz saw an opportunity to expand into the e-document marketplace. “I could help him jump-start that business because of my role in big-time cases,” Ravelo says.

It didn’t occur to her, she adds, that it might be considered inappropriate self-dealing for her to steer MasterCard-related document work to her husband’s nascent company. “At the big law firms, we did favors all the time for clients, arranging summer jobs for their relatives, that kind of thing,” Ravelo says. “I didn’t see any problem with helping Mel.”

Ravelo and Feliz lived large in Englewood Cliffs, an exclusive enclave north of the George Washington Bridge above the Palisades on the Hudson River. In 2006 they paid almost $2.4 million for the spacious house and manicured yard. In October 2010, Willkie announced it had recruited Ravelo away from Hunton & Williams and was also bringing over several more-junior attorneys who worked with her on the MasterCard litigation.

The move to Willkie represented another step up in terms of prestige. With roots in the late 19th century, the law firm has forgone the industry trend toward gigantism in favor of partner profitability. It has 650 lawyers in nine offices in six countries and represents a wide spectrum of businesses, including Bloomberg LP, owner of this magazine. In 2014, Willkie had revenue of $640 million, ranking 64th in American Lawyer’s Global 100 list and representing an impressive 14.5 percent gain from 2013. In terms of average annual profit per partner, Willkie came in 15th, with $2.6 million.

In addition to the standard law firm news release, Ravelo’s joining Willkie merited coverage in the legal trade press. “Two weeks into the job,” the newsletter Legal Bisnow reported, she “tells us that having a Buddha on her shelf reminds her to keep calm, take a deep breath, and focus inside.”

Ravelo continued to show interest in at least certain outward attachments. In the wake of the real estate crash in South Florida, she and Feliz invested $1.6 million in 2010 to buy two waterside condos in Miami, which they intended to flip for a gain, according to the Real Deal, a real estate publication. In November 2013, Ravelo found time to pose for New Jersey social and celebrity publication (201) Magazine. The caption described her as wearing diamond jewelry from Mary Tacorian, a belted Max Mara dress, and Manolo Blahnik pumps while carrying an Hermès handbag from Paris. “I don’t chase trends,” she told the site. “I like classic styles.”

The same year, NBC News in New York included Ravelo in a segment on parents who spend heavily on their kids’ sports aspirations. The television network estimated that she and Feliz spent $70,000 a year on each of their two sons, who attended a baseball boarding school in Florida run by the talent agency IMG. The parents also bought a house in Bradenton near the IMG Academy. “It’s a lot. It’s a big sacrifice,” Ravelo told NBC.

Politically, Ravelo leans left. She served on the board of the National Center for Law and Economic Justice, a New York group that helps low-income families. From 2008 to 2014 she donated more than $500,000 to Democratic candidates and causes, according to Sunlight Foundation, which tracks political contributions. As a black woman, Ravelo remained a rarity at the upper elevations of corporate law. The June 2014 issue of American Lawyer—sporting the cover language “What’s Wrong With This Picture?”—featured her as one of only three black partners out of 131 attorneys recognized by the periodical’s “Big Deals” and “Big Suits” columns over the previous year. On a more upbeat note, the October 2014 edition of Profiles in Diversity Journal included a photo of Ravelo with her arm around a smiling Michelle Obama.

Feliz, meanwhile, was augmenting his document-management business with other pursuits. According to court documents, the DEA received a tip in October 2012 that he and two other men planned to buy 20 kilos of cocaine for $550,000, truck the haul from California to New Jersey, and sell it on the East Coast. On Oct. 22, agents observed Feliz drive up to his Englewood Cliffs house in a black Porsche Cayenne and transfer a satchel of cash from the rear hatch to the car of one of his confederates, who drove to a nearby restaurant and unwittingly delivered it to a DEA informant posing as a courier. The informant transported the money to Los Angeles, where he turned it over to Feliz’s accomplice, at which point the conspirators were arrested and charged with conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute cocaine.

Curious about where the $550,000 in front money had come from, the DEA brought in the IRS, and together the agencies came across the family-run document-services operation, which did business under the names E-Lit and Litigation Solutions. The IRS alleged that Feliz started the supposed vendors in 2008 and had a cousin open a bank account for the businesses in Las Vegas. In New York, Feliz maintained a business address at 110 Wall St. that was little more than a mail drop.

From 2008 through mid-2010, Feliz collected payments from Hunton & Williams, and thereafter from Willkie, investigators concluded. The payments were tied to scut work supposedly done for MasterCard: digitizing and indexing paper documents, burning CDs, and the like. Ravelo allegedly approved most of the outlays.

She says in the interview that as far as she knew, Litigation Solutions “was real. I didn’t want to be involved in the day-to-day operation, but Mel was. I said I would make the referral to my people [at Hunton & Williams and later, Willkie] to try them out.”

At that point in the conversation, Ravelo’s criminal defense attorney, Steve Sadow, interrupts, saying: “That’s far enough for now.”

According to the criminal complaint that led to Ravelo’s and Feliz’s arrests the morning of Dec. 22, 2014, the couple operated the phony vendors jointly and did little or no real work for either of Ravelo’s law firms or MasterCard. Prosecutors alleged that the two funneled most of the fraudulently obtained funds into a joint bank account used to pay personal expenses, including “$250,000 in payments to a jewelry store.”

A subpoena from federal prosecutors landed at Willkie’s midtown Manhattan headquarters in November 2014. Within days the law firm asked Ravelo to resign and launched an internal investigation into what she’d been up to with her husband. Willkie, its spokeswoman, and its outside attorney didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

Another part of the settlement—one that customers would feel—allowed merchants to impose surcharges on shoppers paying with credit cards to recoup swipe fees

In early February 2015, Feliz pleaded guilty to the cross-country drug conspiracy, and a few days later, Willkie went public with what it had discovered during its internal probe of Ravelo. The law firm disclosed that her old friend Friedman had sent Ravelo a stream of e-mail over the years, some of which concerned mundane personal matters like joint family vacations.

But some of the e-mail revealed confidential information belonging to merchants Friedman represented who were suing Ravelo’s client, MasterCard, as well as its rivals Visa and American Express. This mattered because a decade of hard-fought litigation had only recently come to a head in interlocking settlements, one involving MasterCard and Visa, and the other, American Express. The MasterCard/Visa pact, preliminarily approved by a federal judge in 2012, provided for $7.25 billion in damages. Major chain stores such as Wal-Mart, Target, and Home Depot were dissatisfied with the settlement, especially with the future liability protection it provided to the card companies, so they dropped out of the case. These “opt-outs” reduced the value of the pact to $5.7 billion. Another part of the MasterCard/Visa settlement—one that customers would feel—allowed merchants to impose surcharges on shoppers paying with credit cards as a way to recoup swipe fees. A “level playing field” provision required any surcharges be consistent for all cards, a rule imposed by the AmEx settlement as well.

The large retailers that had objected seized on the Friedman-Ravelo back-channel communication as another reason the settlements ought to be blown up and litigation reinitiated. Lawyers for the major chains had long contended that attorneys for the settling class of smaller merchants had suspiciously sold out for too little. Now, they added that perhaps the relationship between Friedman and Ravelo explained why and how the supposed sellout had occurred.

At a freewheeling hearing in federal court in Brooklyn on Feb. 26, Steig Olson, an attorney for Home Depot, suggested that “one worst-case scenario could be that there was a romantic relationship” between Friedman and Ravelo, which compromised their respective clients’ interests. “Ms. Ravelo’s husband has been indicted not only for the scheme that was mentioned here”—the phony-vendor caper—“but for being a narcotics trafficker,” Olson added. “We don’t know if that had anything to do with this.”

Samuel Issacharoff, a professor at New York University Law School who represented Friedman, refuted Olson’s unsubstantiated suggestions. “This is a long-standing friendship,” Issacharoff said. “The families know each other. T

he kids know each other.” He decried what he called “promiscuous character insinuation.”

In separate interviews, Friedman and Ravelo deny any romantic tie. Friedman hasn’t been implicated in the criminal allegations against Ravelo and her husband.

In a written statement, Friedman characterized his communications with Ravelo as routine back-and-forth intended to test out his legal theories. “I acted as I did based upon a verifiably accurate assessment that our communications would benefit [my clients],” Friedman said. “My internal compass is guided entirely by class member interests. … This work entailed no shortage of sidebars, and it required relationships of trust between individual lawyers in opposing camps.”

U.S. District Judge Nicholas Garaufis took a darker view. In August 2015 he rejected the AmEx settlement that permitted merchants to impose a surcharge on customers who use American Express cards as long as the same surcharge applies to consumers using other cards. Garaufis expressed outrage over Friedman’s contacts with Ravelo. (The rejected AmEx settlement would have generated $75 million in fees for Friedman and other plaintiffs’ attorneys, but no money damages for their clients.) The judge noted that Friedman had shown Ravelo large swathes of his confidential case file, including strategy memos drafted by plaintiffs’ lawyers. “Whatever his reason for doing so,” Garaufis wrote, “Friedman’s bringing MasterCard’s counsel into the negotiating process created a conflict between class members and class counsel, and specifically a risk that Friedman, with Ravelo in his ear, negotiated settlement terms that are worse for class members than the terms he might have negotiated absent that conflict.” (Friedman, who disputes Garaufis at every turn, now faces potential civil sanctions for violating a judicial order.)

If the Friedman-Ravelo chatter doomed the AmEx pact, the objecting giant retail chains argued, it ought to have the same effect on the MasterCard/Visa settlement. In trying to salvage the latter deal, Willkie and MasterCard’s other lead law firm, Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, have tried to play down Ravelo’s role. The law firms have said in court filings that while Ravelo led Willkie’s MasterCard team, Paul Weiss attorneys set overall strategy and argued key motions in court.

“That is ridiculous,” Ravelo says. “I was in every meeting, I was on every conference call, and I sat at counsel table in court.”

What’s more, Ravelo says that while helping craft MasterCard’s strategy, she relied on Friedman’s revelations of confidential plaintiffs’ information. “When advising MasterCard and communicating with co-counsel … including regarding the negotiation and finalization of the settlement and in connection with mediation sessions, I drew upon all the information in my possession that affected MasterCard’s interests, including the information I was provided by Gary Friedman,” Ravelo said in a sworn declaration dated Sept. 1. In other words, she claims she used confidences revealed to her by Friedman to try to get a better deal for MasterCard.

If her account is true, the $5.7 billion settlement seems doomed: The plaintiff-retailers’ interests were revealed to—and used against them by—a longtime antagonist. The two Willkie partners who worked most closely with Ravelo—Wesley Powell and Matthew Freimuth—didn’t respond to e-mails and phone calls seeking comment. They haven’t been accused of wrongdoing. Spokesmen for MasterCard likewise didn’t respond. A person designated to speak for the credit card legal team, but only on the condition of anonymity, calls Ravelo’s assertions false. The negotiations and settlement were proper in all respects but for the behavior of Ravelo and Friedman, this person says.

On Aug. 25, Feliz complicated Ravelo’s position by pleading guilty to conspiracy to commit fraud and tax evasion in the faux-vendor case. Feliz, who remains incarcerated, awaits sentencing on the fraud and cross-country cocaine charges. Under his pair of plea deals, he faces 14 years in federal prison. According to Ravelo, Feliz deceived her for more than a decade. Unbeknown to her, she says, he even maintained a secret second family. Ravelo’s attorney, Sadow, wrote in a press release that Ravelo wasn’t a willing accomplice but “acted as Feliz coercively demanded—not freely, voluntarily, or with criminal intent.” Feliz, according to Sadow, “caved to the intense and overwhelming government pressure to implicate Ms. Ravelo.” In an interview, the attorney acknowledges that Ravelo generally is a strong-willed person but says she nevertheless succumbed to “emotional and mental” pressure from her now-estranged husband.

If the coercion defense doesn’t work, Ravelo and Sadow threaten to try a more explosive strategy to foster reasonable doubt about the vendor-fraud case. It’s a long shot but one that could cast unfavorable light on the world of class-action settlement negotiations.

Ravelo suggests she could become a witness in an investigation into whether the MasterCard/Visa settlement talks included unsavory and possibly illegal conduct entirely separate from the fake-vendor business. She says, for example, that she and other credit card lawyers and a court-appointed mediator employed what they called a cram-down strategy, playing stores off each other—smaller stores that cared a great deal about the amount of the swipe-fee recovery vs. pharmacy chains that cared less because they were large enough to negotiate independent terms with the card networks. The defendants worked out a deal with the drugstore chains and then “crammed it down” on the rest of the class on a take-it-or-leave-it basis, Ravelo says.

Although class-action defendants routinely try to divide and conquer groups of plaintiffs, proof of a cram-down, as Ravelo describes it, might raise new questions about the fairness of the $5.7 billion settlement. The person familiar with the credit card legal team confirms that something approximating a cram-down strategy came into play but says no retailers were exploited. The federal judge supervising the process was well aware of how the negotiations unfolded, this person adds.

On another issue, Ravelo says she’s ready to provide evidence that MasterCard and Visa allegedly used private joint defense-strategy sessions to engage in fresh collusion on rates charged to retailers. She says some plaintiffs’ lawyers became aware of this alleged collusive activity, but defense lawyers talked them out of publicizing it in the interest of reaching a large settlement.

Of the fresh collusion allegations, the person designated to speak for the credit card legal team says the judge approved of the defendants working together. Indeed, in a brief order issued on May 20, 2011, U.S. Magistrate Judge James Orenstein brushed aside suggestions by certain plaintiffs that defendants colluded illegally on rates as part of their strategy sessions.

Would federal prosecutors delve into this issue, relying on Ravelo as their turncoat witness? A spokesman for the U.S. Department of Justice declines to comment. Negotiations over a potential criminal plea deal that would reduce Ravelo’s prison term to the realm of several years so far haven’t borne fruit. On Nov. 5 a federal grand jury indicted Ravelo on fraud and tax-evasion charges related to the phony-vendor scheme. Under the indictment, Ravelo faces up to 25 years in prison.

If Ravelo does go to trial, she threatens to expose other damning practices in high-stakes litigation. The collateral damage to former clients and colleagues appears to be of little concern to her as the likely-to-be-disbarred attorney seeks to avoid a future behind bars. “People don’t know the whole story,” she says. “I’ll tell it because I have to—my life and my children’s lives depend on it.”

No comments:

Post a Comment