Over the past 20 years, releases of new Windows operating systems have been marked by midnight sales parties, junkets crammed with reporters, and Microsoft’s biggest marketing campaigns. The introduction of Windows 10 on July 29 is much quieter: no ringing the Nasdaq opening bell, no promos with sitcom stars or Rolling Stones songs—just 13 parties around the world to thank volunteers who’ve helped debug and refine the operating system during the past year. “Having a big launch with celebrities, it might be newsworthy, but it’s not necessarily the step to a billion happy and engaged Windows users,” says Windows chief Terry Myerson.

Microsoft has promised shareholders that Windows 10 will reach 1 billion users within three years—which would give it the fastest adoption rate ever—even as the company shifts its focus to other products. It’s relying in large part on the 5 million volunteer bug testers, known as Windows Insiders, not only to make Windows 10 better but also to build loyalty for the OS. It’s a humbling acknowledgment that as consumers shift from PCs to smartphones and tablets, the software synonymous with Microsoft isn’t the required tool it once was. In 2000, Windows ran on 97 percent of the world’s consumer computing devices including phones and tablets, Goldman Sachs estimates; today, it’s under 20 percent.

Under Chief Executive Officer Satya Nadella, Microsoft has begun to recognize that the biggest competition for a new version of Windows is no longer the previous version of Windows. To better spread Microsoft’s influence beyond its own operating systems, the company has acquired several makers of iOS and Android business apps and introduced new versions of Office apps on iOS and Android first. The OS division’s marketing chief, Yusuf Mehdi, is talking about winning customers back from “other ecosystems,” such as those created by Apple and Google. To do that, Microsoft has tried to make Windows 10 as intuitive and inviting as possible.

Windows 8, released in 2012, annoyed users by making the PC into a tablet, eliminating familiar features like the Start Menu in favor of a touchscreen system based on taps and swipes that only a small percentage of PCs could take advantage of or accommodate at all. The new edition restores the Start Menu and lets users switch more easily between the touchscreen setup and a more traditional point-and-click interface. It’s a lot more natural than the Windows 8 setup, if not exactly revolutionary.

Microsoft has also replaced its decrepit Web browser, Internet Explorer, with a new one called Edge, which is missing some customization options at launch but otherwise compares favorably with Chrome and Safari. The company’s Siri-like virtual assistant, Cortana, is built in, so you can bark out, “Tell Tim I’m running late,” and the OS will send an e-mail. Say, “Add milk to the grocery list,” and, with the help of GPS, Cortana texts your phone a reminder to buy milk when you’re in the parking lot at Stop & Shop. For its first year on the market, Windows 10 is free for consumers who have an earlier version of the OS, or $119 for those who don’t.

The biggest change was last September’s creation of the Windows Insider program, the group of consumers and business customers who agreed to download a series of early versions of the OS and try them out. Members sent feedback on each after using it for about 10 hours, shaping Windows 10 to a degree that would have been unimaginable for Microsoft a few years ago. The new OS has received a “surprisingly positive response” from companies, says Steve Kleynhans, an analyst at researcher Gartner. Easing people into the new interface has helped assuage fears about the notorious bugginess of past Windows releases.

Microsoft could use a hit. On July 21 the company announced a record $3.2 billion quarterly loss on $22.2 billion in revenue, owing to an almost total write-off of the Nokia phone business it bought for $9.5 billion in 2014. Microsoft is massively scaling back its in-house phonemaking and cutting about 7,800 jobs. And while it’ll be time for holiday shopping before Dell and Hewlett-Packard have new PCs ready to take full advantage of Windows 10’s new features, the OS still brings in serious money. Chief Financial Officer Amy Hood said in April that it’s now worth about $15 billion a year, down from about $19 billion in 2013, the last time Microsoft disclosed Windows division revenue. Ninety-two percent of the 300 million PCs sold around the world each year run Windows, Gartner estimates, down from 95 percent two years ago.

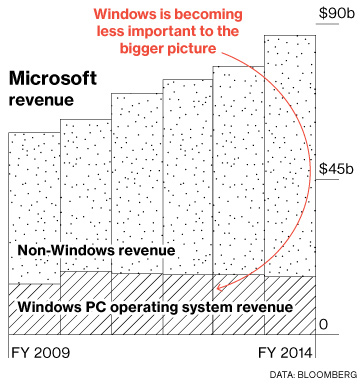

Following his earnings report, Nadella told analysts that while Windows 10 would restore the OS division’s revenue growth, its effects would mostly be felt at least two quarters from now. He appears more focused on the company’s future beyond Windows: In June he distributed a mission statement to employees that listed the OS third among the three priorities of his tenure, behind “productivity services” (including Microsoft Office) and cloud platforms. “Windows has moved from a lead role to a support role,” Gartner’s Kleynhans says.

The Windows team continues to invest in research and development, including on projects beyond the PC, such as augmented-reality goggles that display holograms, and 84-inch touchscreen computers for a $20,000 corporate conference room setup. Windows chief Myerson says he’s trying to make sure Microsoft’s OS will be “the best home” for Office and Skype, among other company products.

In part, he says, that means following the process of regular updates and improvements that began with Windows Insider, as opposed to rolling out a new version of Windows every few years. (Corporate users who don’t want to be bothered to regularly update their systems can opt out.) It’s possible there won’t ever be another update so big that it requires a kickoff party. “Let’s put it this way,” Myerson says. “There’s nobody working on Windows 11.”

The bottom line: With Windows 10, Microsoft is trying to turn around a two-year slide in OS revenue, from $19 billion to $15 billion.

No comments:

Post a Comment